Blogs

The Convergence of Ecosystems and Textiles

01 Jan 24

By Owner

Time : 450 days 50 minutes 32 seconds ago

“The knot, or ‘gaanth’ or ‘Idut-pa’, is a recurring occurrence in Himalayan cultures. It carries not just spiritual but pragmatic importance.

Where does fashion stand in discussions about sustainability, the context of craft-centric design, and the pressing issue of climate change?

In profoundly insightful dialogues among a panel of dynamic individuals who exemplify change, empathy toward culture and ecology, and advanced design thinking, there are numerous lessons to be gained, not only for designers but also for the conscientious citizens of tomorrow.

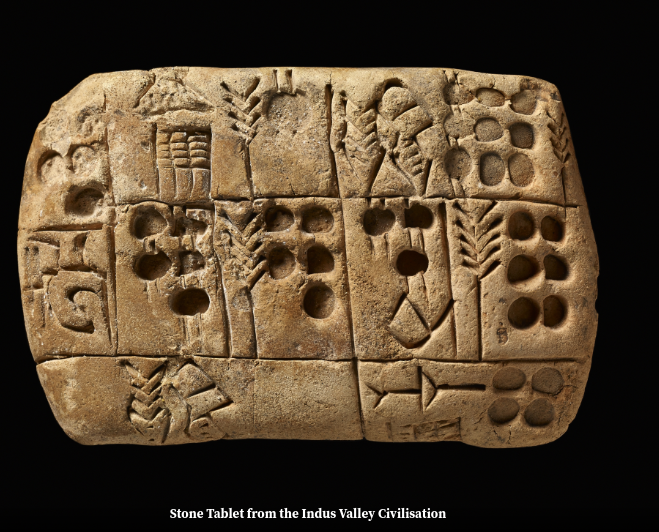

The narrative around craft often leans towards sympathetic primitivism, portraying it as an arduous process involving handwork and painstaking devotion. What is amiss, however, is that these practices were never tailored to meet market demands. They originate from the lifestyles, belief systems, and choices of people exposed to significantly different environments. Thus, a shift in understanding is paramount when consciously engaging with this space.

A poignant example is the increasing demand for Pashmina. Earlier, the ratio of sheep to goats reared in Ladakh was 1:5; now, it has reversed to meet the surging demand. This change affects pastoral lands, but it often lacks compatibility with some practices that could benefit from deliberate design and systemic intervention. A country with a rich heritage of handmade practices and products that the world values often lacks the infrastructure and systemic support necessary to scale, promote, profit, and, most importantly, impact at the grassroots level. Farmers expected to deliver five times their earlier produce still operate with tools designed for earlier quantities.

Furthermore, sensitivity to and preservation of cultural sentiments are undeniable aspects when working with a community and its indigenous practices. A designer can ensure a more enriching outcome by involving and learning from the artisan. This entails not only giving due credit but also emphasizing that creation rarely occurs in a vacuum. Co-creation and collaboration lie at the heart of good design, and outcomes are seldom aesthetically, sensitively, and philosophically aligned when actions are taken in isolation. People are at the heart of every endeavor; we are made by and of people.

Our everyday language and media positioning are increasingly oriented toward greenwashing. The inherent frugality and “jugaad-ism” embedded in our ethos have become adjectives on price tags and campaigns, supposedly meant to turn heads. The question to ask is, how do you function or align with these so-called values if you’re playing the gamble of inventory and anticipation? How do you define design when your practices don’t explicitly incorporate sustainability unless paired with the phrase “unique selling point?”

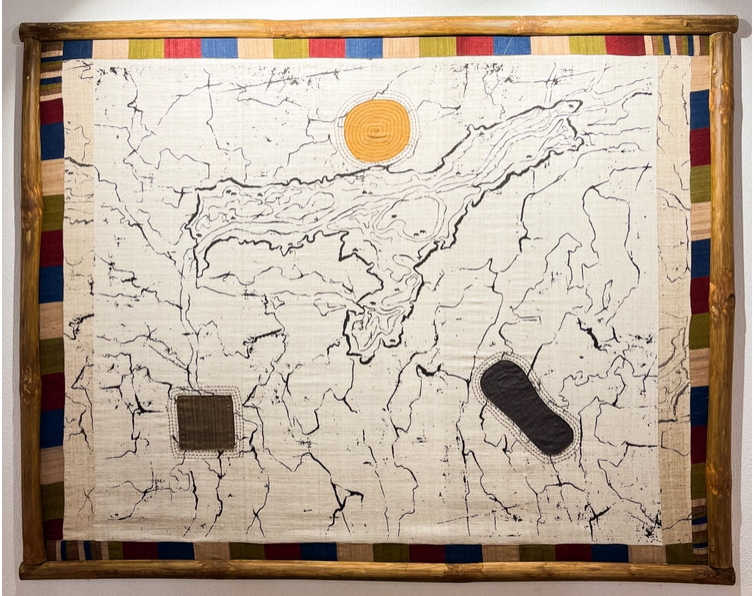

The subsequent exhibit showcasing the living heritage of the Eastern Himalayas was a cultural immersion into their practices and philosophies through photographs and audio-visual media.

The Himalayan Fellowship for Creative Practitioners, an endeavor launched by the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art in collaboration with Royal Enfield, invites creatives across the spectrum to work at the intersection of culture and ecology. Owing to the vicissitudes that these landscapes are subjected to, like over-tourism, climate change and biodiversity, and the threat to traditional knowledge systems, this fellowship aims to extend support as a response to such urgency by creating uniquely tailored solutions.

Objects of cultural significance were dotted across the exhibit as a visual mouthpiece of indigenous lifestyles. Besides utility, these objects are ingrained with mythological narratives which endow them with a symbolic space.

The tale of two Headgears- finally brings together two juxtaposing worlds through form and aesthetic.

Photographs by Aakriti Gupta and words by Harini Srinivas.