Blogs

An Indian Lexicon for Design

10 Jan 24

By Owner

Time : 483 days 21 hours 43 minutes 46 seconds ago

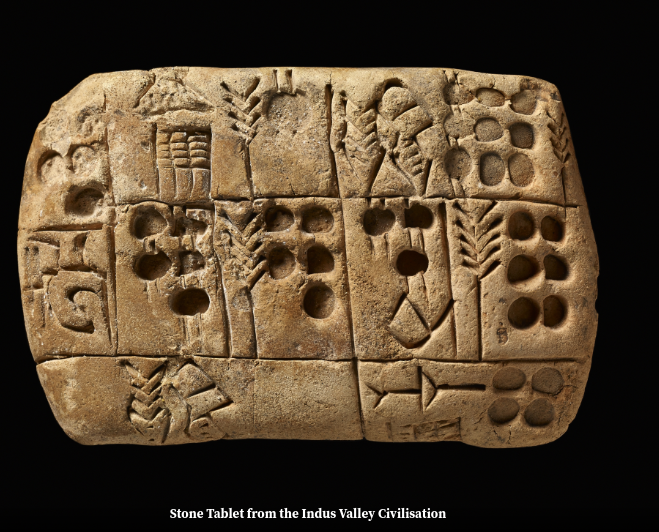

The remnants of ancient civilizations are a testament to our proclivities to imagine, explore, understand and express as a species. Archaeological sites like the Göbekli Tepe, Egyptian hieroglyphs, stone tablets from the Indus Valley Civilization,

The remnants of ancient civilizations are a testament to our proclivities to imagine, explore, understand and express as a species. Archaeological sites like the Göbekli Tepe, Egyptian hieroglyphs, stone tablets from the Indus Valley Civilization, and the intriguingly elusive Voynich Manuscripts are all examples of attempts to transmute, preserve, and communicate knowledge and culture. Besides, an examination into tribal cultures that to date preserve their native practices suggests a profound degree of meaning imbued in their costumery, ornamentation as well as body inkings. The above examples illustrate the ubiquity of symbols and visual tools of dissemination. It also underscores the fact that these practices weren’t arbitrary and cosmetic but concerned themselves with what gave life meaning. The human impulse to create and communicate predates modern-day graphic design.

However, the Indian lexicon never truly had a word for design; it was an invention of the west. Graphic design in particular was one that gained traction with the invention of the printing press. The 1920s in particular was a pivotal period for posters, printmaking, and bringing art into the domain of business. Design was essentially evolved into art viewed under commercial and technological constraints. The principles that soon came to govern “good design” were delivered within the paradigm of said considerations.

As a former student of a design education system that encourages students to look toward heritage practices yet continues to look westward, I observe a marked discontinuity in contextualizing pearls of wisdom that have existed in our culture for centuries. This isn’t so much about the need for all students to have an inherently Indian visual aesthetic but to deeply understand and embody the universality and spiritual rootedness that the Indian parlance has governed.

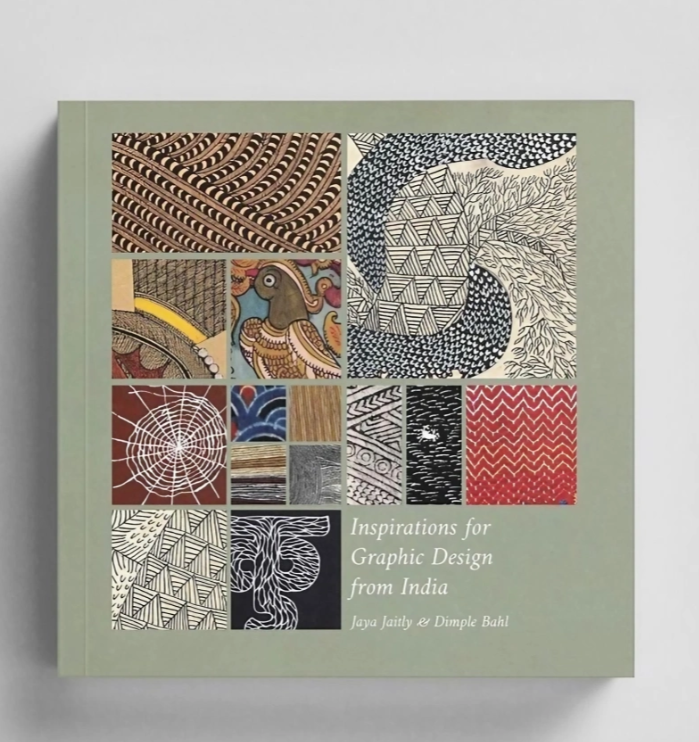

“Inspirations for Graphic Design from India” by Jaya Jaitly and Dimple Bahl was intellectually invigorating. It helped me understand the philosophical gaps that I lacked as a designer and brought about a deeper cognizance of the varied craft, textile, and heritage practices that exist in our country. This is definitely a book that I would return to ad infinitum.

In writing about this book and my learnings from it, I hope to help students glean a greater insight into the principles of design. It can often feel clueless or abstract but the narratives mentioned in this book make understanding the elements and principles a lot more palatable. This blog in no way attempts to summarize this book, and I believe it won’t be possible. Every line in the book offers profound wisdom and truly encourages one to undergo a deep reflection. This blog, however, is only a humble invitation to the reader to embark on an examination of values. It aims to offer cues and a few nuanced takeaways from the book so that perhaps we all begin to view creativity as an oblation.

Bindu

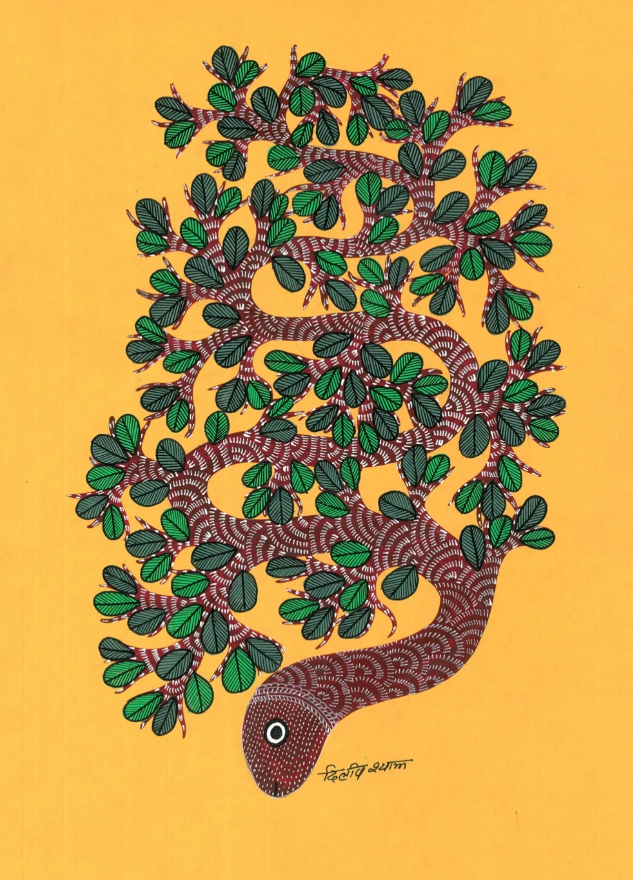

Bindu, or the point, the design equivalent of the atom (a belief in the Vaisesika school of thought). Equated to the primordial beginning, its depiction is also considered a symbol of Soma- encompassing the essence of creation. In script it manifests itself as the anusvara, a nasal sound. It is the focal point, one that draws and directs the gaze. When used in a context that directs one outward, the Bindu becomes a point of expansion, when one sojourns inward however, the Bindu becomes a point of intense focus. The point is also the genesis of the line and subsequently shapes. All that is tangible builds itself on the foundation of the point. Sadhnana Bindu is esteemed as the origin and summit of all conscious endeavors.The Gond art form is a throbbing example of a potent visual vocabulary comprising almost entirely of the Bindu.

Rekha

In a very profound sense the point and the line are indistinguishable. The Rekha is primarily one that establishes interconnectedness. It’s fascinating to observe the essential role of line in the artistic process, from the conception sketch to their final reemphasis marking the completion of the artwork. Furthermore, the line is also an indicator of energy. Vertical lines depict the nature of fire, diagonal lines that of wind, and horizontal lines that of water.

The descriptions of defects (dosa) in paintings it is said that feeble, broken, crooked, and too thick lines are to be avoided since they don’t produce a good painting. I believe this doesn’t necessarily speak of the inherent undesirability of such lines but caution and appropriateness one must exercise when communicating with the line.

Aakaar & Aakriti

n the west shape and form are defined in terms of dimensions, characterizations are a lot more fluid and nuanced in the Indian perspective. All aakaar exist on the plane that begins at sakaar (manifest) and nirakaar (formless). The distinctions of organic and inorganic shapes are also encompassed in the nuance of the words- aakaar and aakriti, though they aren’t limited to just that. Aakaar is known to be more definite while aakriti is related to the indefinite. Aakaara is also known as the finished stage while aakriti is the stage of framing. So by this definition all that is geometric falls under aakaar and shapes like clouds come under the umbrella of aakriti.

Shapes have been a tool of delivering philosophical ideas. Vital examples are: A downward triangle denoting chaos, feminine energy, or Shakti. The upward triangle by itself is a symbol of the triumvirate- Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva. The Sriyantra- Nava Chakra conveying the nine rungs connecting the seeker to the spirit and superlative. In essence, geometric configurations illustrate the journeys of self-discovery.

Additionally, the now popular theme of adult coloring books and tapestries alike- the “mandala” is also fundamentally an amalgamation of shapes designed to promote concentration. It is considered to be a link between the individual (Atman) and the universe (Brahman).

Shunyata & Ananyata

The void and the infinite are nothing but one. Shapes and forms exist but in an indispensable relationship to and with space. Space is a binder of elements. The mathematical manifestation of the void is seen as zero. Seemingly inconsequential in itself but of immense value in decimal notation.

The presence of absence of space in a design is integral in asserting the hierarchy of ideas and emphasis. Emptiness is essential in comprehending the whole. A calculated and conscious use of space also is a mark of reverence, and a manifestation of grace. Space is perhaps the most non-dual of all the elements of design mentioned. In some sense, it grapples with the paradox of both being and non-being.

Manuscripts are a beautiful example of the conscious use of space. A kalamkari block also exemplifies the integral role of emphasis that is exerted by the presence and absence of space.

Sanrachna

Texture in art is a creation of the line. However, it also exists independently in each “tactile or tangible” art form, portraying its characteristic through its texture. The bark of a tree, the surface of a leaf, the buds of cotton, all possess a unique tactile quality. A fabric woven with said cotton depending on how its yarn was spun invokes a distinct feeling of touch perception. A confluence of varied lines and dots can potently establish the “visual feel” of tactual sensation.

Godna, a form of body inking, tattooed on the bodies of poor women is said to provide ornamentation in the absence of jewelry. Besides, tattoos were also of significance in literally “etching” the events of one’s life onto their body be it ideas one is closely affiliated with, symbols of protection, and mementos of cherished individuals.

Rang/Varna

Color and India are synonymous in some sense. It is a topic of interdisciplinary interest and finds itself at the crux of spirituality and geography. Krishna is associated with the color of the night- also known as the attractive one is popularly depicted in navy and darker shades of blue. Similarly, Shiva is known as the Neelkanth– denoting the poison he holds in his throat, from the anecdote of churning of the milk ocean. Vishnu is associated with opulence and is observed bedecked in yellow- a cloth woven with the rays of the sun. Vermillion, a color of good fortune and auspicious beginnings is the tilak. Red is the color of devi, primordial in the nuptial ceremonies, a symbol of fertility, signifying royalty, courage, and strength.

It is also fascinating how our ancient texts as opposed to devising nomenclature for colors resorts to figuratively describing them: “The two warriors dripping with blood looked like two kimcuka (Flame of the Forest) trees blooming on the mount of snow.” This is something that I find of particular ingenuity- it reminds of the many disagreements I’ve had with fellow artists and designers on what constitutes a particular colour which perhaps would resolve itself through similar descriptors.

In illustrating the many examples of ancient, artistic practices, the book poignantly decolonizes our perspective, understanding, and language of design. It examines the many layers of thought and practice that goes into conceiving a piece of work. Further, it also draws particular attention to the distinctions drawn between art and design. Is design only defined by its commercial value? Is an act of authenticity- of personal and communal significance, however devoid of the monetary not render itself worthy of being accepted as design? Is design not any conscious undertaking which is an answer to life?

This book, I believe, is also a gateway into educating many households where the creative career is looked down upon. The realm of pursuing the arts is often delegated to the supposed academic underachiever. In circles of doctors, engineers, lawyers, and accountants, the artist and designer are hardly given a modest consideration. “Inspirations for Graphic Design from India” is a book I’d thus prescribe to not just students of design and the artistically inclined but to educators at large and anyone who wants to broaden their horizons.

Words by Harini Srinivas